Frelard’s industrial zoning is inappropriate

Have you ever noticed in Frelard just how close we are to the water? A big portion zoned exclusively for industrial-use is blocking our enjoyment of the nearby waterfront for no good reason. It may have been reasonable a hundred years ago—bustling maritime services, manufacturers transporting cargo, employers of many local residents—but it doesn’t today. The reality here is vacant lots, “For Lease” signs, and homeless encampments ironically next to empty buildings. Upzoning for mixed-use would acknowledge contemporary industries; create housing, jobs, and bolster funding for social services (Industrial Rezoning in US Cities, Manhattan Institute).

Across Leary Way NW, near small businesses and homes, is endemic vacancy. Why not allow industrial-mixed in Frelard?

In 2023, Seattle’s industrial zoning became more restrictive (New laws limit big box stores in Seattle’s historic maritime and industrial zones, Axios). It happened despite data forecasting zero or negative maritime growth—from employing 1.1% in the Puget Sound region in 2010, to .8% in 20 years (Seattle Maritime and Industrial Strategy: Updated Employment Trends and Land Use Alternative, Seattle.gov). Also, despite excess industrial land across the Seattle Metro with over 400 million square feet available (Seattle industrial market report, Kidder Mathews). The good news is that zoning policy isn’t immutable. Earlier this year, mixed-use development was approved in SODO’s industrial zone (Seattle to get new ‘Markers’ District’ with affordable housing, industrial workspaces near T-Mobile Park, KUOW). So, if SODO can upzone, than so could Frelard!

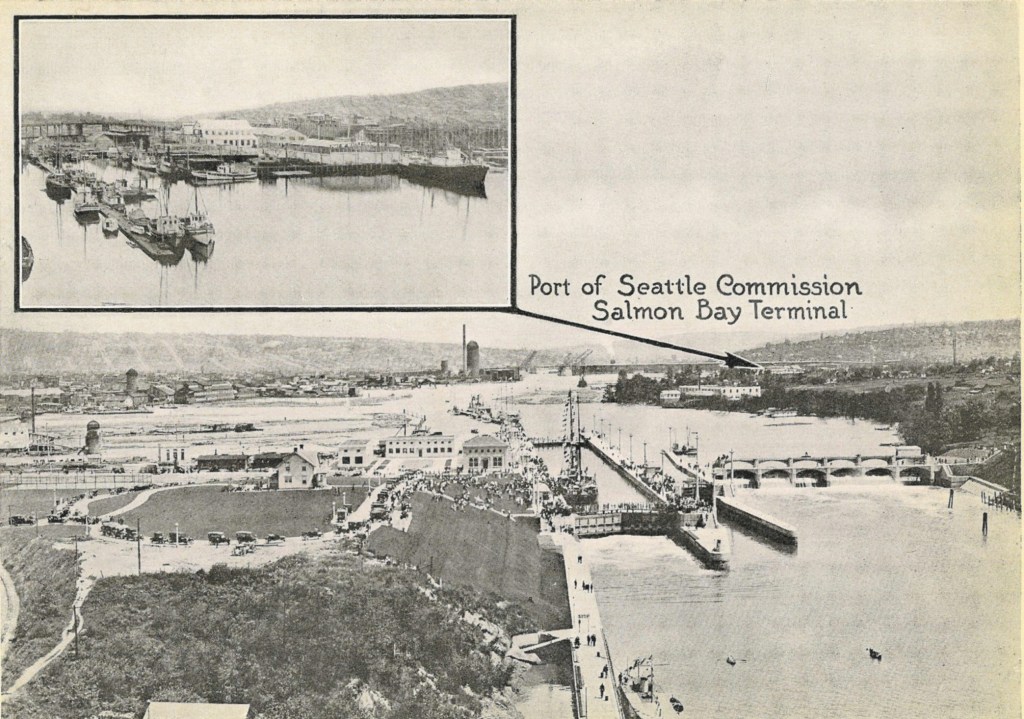

1919 photograph of Frelard (source wikimedia). See Gasworks at the center in the distance? Fremont is just to its left and the nearer large undeveloped wet area is Ballard. A lot has changed in a hundred years; why not free our potential to keep changing?

What are we waiting for? A lot of valuable land in Frelard is being reserved for an industrial manufacturing renaissance. What used to be partially a tidal zone before the Ballard Locks was built around 1917 (Working Waterfronts, Maritime Washington), a few years later was reserved for industrial-use only. Unfortunately, little did we know that the Industrial Revolution was at its end (Industrial Revolution, History). Walk around and you’ll find homes in industrial zones, built before zoning laws, never displaced by hungry industrialist. Today, industry moves in another direction. It’s about time we amend our zoning to cultivate a more vibrant Frelard!

Like Frelard, Williamsburg in New York had a declining need for industrial land post WWII and the advent of containerization, so they upzoned in 2003 (Up-zoning New York City’s mixed-use neighborhoods, Journal of Planning Education and Research). Above is a picture from 2022 of a vibrant pizza restaurant where, below via Google, is the same spot ten years prior. Imagine how vibrant Frelard could be in a couple decades!

In 1991 Salmon Bay Steel closed after 29 years of operation (Salmon Bay Steel Kent, WA.gov). The site was too expensive and small to attract new Heavy-Industry and later became a Fred Meyer grocery store (Plot thickens as Fred Meyer seeks to build store, Seattle Times). Just across the water, Ocean Beauty Seafoods cannery in 2018 moved after a hundred years of operation, citing improved logistics in Renton (Seattle and its relationship with industrial land, UW). In its place is a new space for a creative economy (West Canal Yards, Arcade NW). The likes of which could easily co-exist with housing residents if it were allowed.

Areas in pink are liquefaction prone, which isn’t surprising since Frelard used to be a tideflat. There are many technologies for developing safely on this type of land (Reinforcing the ground beneath our feet, UW)

Upzoning doesn’t necessitate exterminating industry. Baltimore, for example, created “Industrial Mixed-Use” zoning in 2017. Their policy reserves at least 50% of any ground floor for industrial-use and ensures environmental cleanup (Mixed-use zoning, Sustainable Development Code). With the right policy for Frelard, allowing residential development near industry is possible.

Some Frelard residents already live like its Industrial Mixed-Use zoned (2017, Port of Seattle). However, current zoning prevents homeowners from adding dwelling units, and developers from turning vacant lots into vibrant mixed-use places.

What if it’s polluted? Land contaminated by Heavy Industry is also known as brownfield sites. Known areas of contamination and cleanup progress can be found here: Department of Ecology, WA.gov. It doesn’t matter how land will be used in the future, or who occupies it, pollution warrants cleaning. If not for people’s health or the environment, then because it increases nearby property value 5-15% (The value of brownfield remediation, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists).

Note, there is unfortunate precedent for decreasing standards for low income housing. Some developers in the past have deceived people into believing the government kept impossibly high standards preventing affordable housing (Brownfields cleanup standards, Fordham Environmental Law Journal). Cleanup does incur a cost, but there are many ways to do it (Nature based solutions for contaminated land remediation and brownfeld redevelopment in cities, Science of the total environment).

Below, in gray-blue is the Maritime Manufacturing Logistics (MML) zone geared towards maritime-use and Heavy Industry (Industrial & maritime strategy, Seattle.gov). Left, a 2016 map shows that few lots were being utilized for such purposes (Port of Seattle). Today, one parcel operates Heavy Industry (Snow’s Seattle yard hits 100 build milestone, Workboat); it exists harmoniously with residents steps away.

The cost of blocking mixed industrial use zoning:

- Ignores people trying to live there anyways, despite lacking sanitation. In 2023, homelessness costs $17,900 a person in Seattle, yet the number of people becoming unhoused continues to rise (Despite big budgets, homeless agency is clueless in Seattle, Pacific Research Institute). For context, prisoners cost $63,600 a person in Seattle (As Washington’s prison population shrank, the cost of incarceration went up, KUOW). Public school costs $18,900 per student in Seattle (Seattle Public Schools, US News). Community college cost taxpayers $3,700, plus the students themselves pay $11,300 (Seattle Colleges). Meanwhile, upzoning to decrease homelessness costs $0.

- Actually, upzoning generates revenue—so there is an opportunity cost (e.g., wages, sales, taxes, etc.) for preserving unused industrial land (The economic consequences of industrial zoning, Land Economics).

- Ignores the needs of bigger and faster growing industries than maritime and manufacturing (Employment security department, WA.gov).

- Vacancy is liable for potential injuries, increased pests, crime, and anxiety (More than just an eyesore, Journal of Urban Health).

- Blocks access for local residents to enjoy Frelard’s waterfront—like they used to a hundred years ago. Walking along a waterfront can significantly reduce stress (The restorative health benefits of a tactical urban intervention: An urban waterfront study, Urban Environment and Health).